The Poison Plume

Charles strides out of the Chiller Building excavation shortly after the plume was discovered. All construc-tion activity had stopped.

Now we jump back up to September of 1993. By then HH&N had been underway for three months. The concrete column fiasco was in full bloom. Across the street the chiller house excavation was nearing completion. The cut-off wall subcontractor, Spencer, White & Prentis of Virginia, had installed the wood lagging on the sides of the giant hole to protect the car wash property, including the steel tie rods under the detail shop. Dirt sub Sonny Wadsworth and his minions had the excavation over 20 feet deep and their huge trucks were hauling away the spoil like army ants. Jerry Gilbert, our local test lab guy, had his staff on site evaluating all excavated earth that was to be used as backfill elsewhere on our project. Things in the chiller plant hole were going as well as might be expected. Then it happened . . .

Jim Lewis, who worked for the test lab, noticed that a load of earth being used for backfill in the basement of the Tower had a foul odor. It made some of the workers sick. Lewis determined that the load had come from the chiller plant excavation in progress across McDonough Street, and he walked over to investigate. At the chiller site he encountered Sonny Wadsworth’s oblivious forces, who said, “Yeah, the dirt had smelled bad for two days.” In fact, they had already hauled 19 truckloads of it away, bad smell and all. Jerry Gilbert was quickly called to take samples and determine exactly what they had encountered. That was September 8, 1993.

The next day word came back that the soil contaminate was tetrachloroethylene, a hazardous chemical used by the dry cleaning industry. Apparently, in days of yore, some laundry southeast of our site had disposed of its used dry cleaning fluid by pouring it down an old cistern. The resultant chemical flume was slowly traveling northwest in a water-bearing sand strata and heading for the Alabama River.

This clip of Jymalyn appeared in the Montgomery Advertiser some seven years after the Tower fiasco,

when the ADEM focus had shifted to the Coliseum Plume episode.

The paranoia of the time demanded a knee-jerk over-reaction. Work in the chiller site was stopped. The Alabama Department of Environmental Management (ADEM) was notified, and ADEM promptly notified the EPA in Atlanta. The environmental zealots were in their glory. White garbed ADEM technicians rushed to the site to take samples and assess the situation. Fortunately for yours truly, the Owner’s Rep, Ron Blount, had advised me at the outset that this affair had such potential for disaster that he was personally going to handle the matter and deal with ADEM. At the PH&J office we all laughed at the furor–in the Forties and Fifties we cleaned our drafting instruments with an almost identical chemical, in pure concentration yet–not this 500 ppb stuff.

A young woman named Jymalyn Redmond headed ADEM’s site assessment unit, and apparently she and her staff were a little overbearing. They enjoyed their new role, refused to speculate on prospects of restarting the job, and otherwise added to the RSA’s frustrations over this undeserved misfortune. It was charged that she even allowed the press unfettered access into the hole. Ron Blount was especially perturbed by all this, and he became highly agitated.

Over the next few weeks relations between the RSA staff and the ADEM site team became more and more strained. So strained, in fact, that Jymalyn ultimately reported to Leigh Pegues, head of ADEM, that Ron Blount had threatened her physically and she was now afraid to enter upon the contaminated ground. Gossip of the threat permeated the ADEM headquarters, where all of the employees were members of the Retirement System. At the construction site, charges of mismanagement by Jymalyn were spread, and the gate in the fence surrounding the hole was locked shut, so she and her staff could not have gotten in even if she was not afraid. The affair shaped up to be a public relations and financial disaster of the highest magnitude.

All the while, HH&N, which was suffering the dire concrete problems previously reported, viewed this episode as a glorious opportunity to deflect criticism from itself and to make a ludicrous, granddaddy claim against the RSA for stopping the job and disrupting their work schedule. “Unforeseen Conditions” was the legal hue and cry, but goodness knows, their schedule could hardly be made any worse than it already was.

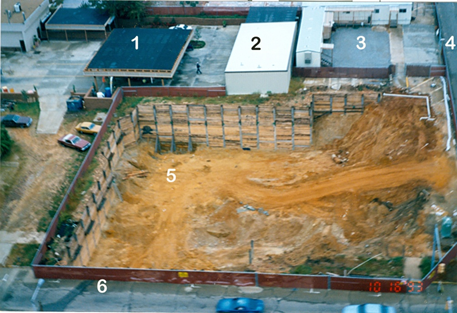

The Chiller Building excavation around the time of the Dirt Problem. Mark 1 is the Madison Car Wash operation shed. 2 is the car-wash detail shop (the footing of which I claimed extended onto RSA property). 3 is the Job Office complex of the Architect’s and Owner’s Rep Staff, ground which later became part of the RSA’s Pavilion Park. Number 4 indicates Monroe Street. 5 shows where the poison dirt was encountered. Mark 6 denotes the edge of McDonough Street.

The Confrontation

Leigh Pegues, head of ADEM and a golfing buddy of Dr. Bronner, became incensed when he learned that his young lady engineer had been threatened at the Tower site by an RSA minion. He immediately called Dr. Bronner for an explanation. I must admit at this point that this same Leigh Pegues was business manager at Judson College when PH&J began doing all its work there in the Sixties. And he was Mayor of Marion when we did the city hall there. He and PH&J were old friends.

Thus it was on the morning of October 15, 1993, that I received an urgent summons to the RSA Fifth Floor for a meeting with Bronner. According to his Nibs, he had that very morning directed Ron Blount “to get out of ADEM’s face, to go play golf somewhere, and to no longer represent RSA in the matter”. Bronner went on to say that yours truly was to henceforth represent the RSA in dealing with ADEM, and that I was to “pour oil on troubled waters”. “Furthermore,” he continued, “I’ve told them that they may dig on the site again this very afternoon. You arrange it.”

I hurried back to the office and quickly ascertained from an HH&N superintendent that they had no objections to ADEM technicians being admitted into the chiller hole, but that their standard release form and safety rules were still in effect. That meant that every member of Jymalyn Redmond’s team would have to sign a release and wear a hard hat. That was an important issue because we had insisted throughout the ordeal that HH&N still had custody and control of the chiller site, and I did not want to give them an excuse to relinquish that responsibility.

That afternoon I met Jymalyn and her coterie of technicians in the middle of Monroe Street in front of the chiller site gate. To avoid any insult or inconvenience to the ADEM party, PH&J’s field staff had secured a tablet of the contractor’s release forms for them to sign. We even had a half dozen extra hard hats available to loan the group. It was not enough but was all we had. I was backed up by my staff of four men, Jymalyn by her group of ten. It shaped up to be a real confrontation. She was testing her power and I was guarding mine.

Jymalyn haughtily refused to sign a release form, and said she did not intend to wear a hard hat. “Well, then, Jymalyn,” I responded, “we are not going to unlock the gate and admit you to the site. This property is under control of the contractor, not us, and you must follow his rules.” I winced inside because this was not pouring oil on the water.

Our two groups eyed one another for a few moments. It was like a shootout at the OK Corral. Finally I reopened the dialogue. “Jymalyn,” I asked, “does ADEM have police power?” When she answered in the affirmative, I said “Well, you had better exercise it and order us to unlock the gate in the name of the State.” She did, and we did, and her party solemnly filed down into the excavation to resume their investigation. Later she faxed me a copy of her legal right to issue such an order.

Thus did the day end. I had followed Bronner’s directive to get ADEM onto the site. I had not violated HH&N’s custody, nor created for them nor RSA, nor PH&J, any liability in the matter. Jymalyn went back to her office to report that her authority had been re-established.

Of course, we had to caution the ADEM troops not to probe too close to the cut-off wall ere they undermine it. When I got back to my office, Leigh Pegues called to learn what had happened. I told him what had transpired, and he found no fault with my position.

At least for that day I had calmed the waters and smoothed a few ruffled feathers.

The Newspapers and Television Stations Reveled in all aspects of the Dirt Saga. There were articles and feature stories every day for weeks.

Twenty Yards of Expensive Dirt

The roiling waters might have been somewhat calmed, but this hellish dirt problem would not go away. This is written several years later and the issue still looms as a giant threat. But it was bad enough in ‘93 and ‘94. As a result of PH&J’s design concept to bury the chiller plant, the mass excavation reached 22 feet and exposed the evil plume. That set off the encounter with ADEM forces, and the RSA was forced to pay the contractor to extend the cut-off wall down another five feet along the car wash detail shop. Everyone suspected that ADEM was blowing all this out of proportion and wanted to turn downtown Montgomery into a Federal Superfund Site.

However, for all the hullabaloo, ADEM was able to find only 20 cubic yards of additional contaminated soil. Nonetheless, the full force of the government was brought to bear on this single unfortunate truckload. Never mind that Sonny Wadsworth had already gone off with 19 truckloads and spread it who knows where. The twentieth load was dug up on ADEM’s watch and it would damn well be disposed of correctly.

To advise us through all this clamor and to protect us from Jymalyn and her crew, we gave Jerry Gilbert and his test lab the additional duty of verifying the ADEM results. We also hired local engineer Haynes Kelley and his firm to give us advice regarding the chemicals. In addition, we sent our civil engineer into the hole to survey the bottom to prove what and how little was dug up. The survey was to protect us from HH&N. Pegues urged us to employ expensive out-of- town experts, but for now that was not in the cards.

Last, but not least, we hired one Robbie Wood, a “Licensed Hazardous Waste Hauler” and the RSA paid him top dollar to haul the load to Emelle in Sumter County, Alabama for burial. However, the Emelle dump had a waiting list and the RSA could ill afford a delay. So instead we made plans to ship our foul dirt to the Marine Shale Dump in Louisiana. When word of this change in plan reached ADEM, Leigh Pegues called and told me we were about to make a terrible mistake. He said that Marine Shale was run by crooks so notorious they had been castigated on the TV show “60 Minutes”. Well, we certainly didn’t want our precious dirt going to a bad place like that.

Finally, it was decided that we should ship our modest load of notorious dirt to the Invatech Facility in Michigan, where it could be incinerated to death. By this time we all knew that Tetrachloroethylene completely dissipates on contact with the atmosphere, and that probably there was none of it in the defiled 20 yards. Nevertheless, things had now gone too far and Robbie Wood and his rig left for Michigan, doubtlessly frightening the inhabitants of every town through which he passed on his thousand-mile trip. I am sure that the Michigan workers shouted “burn, baby, burn” when the Alabama soil went into their fiery furnace.

Redesigning The Building

It was bad enough that we suffered three months of delay–which HH&N blatantly tried to turn into a $470,000 claim. This despite the float time and critical path issues which made a complete mockery of such an absurd demand, and despite the 111 days of liquidated damages (at $12,000 per day) waived by RSA to the tune of $1.3 Million. And it was bad enough that the Retirement System had to spend a quarter million dollars hiring extra consultants and test labs, drilling test wells for ADEM, and hauling dirt to Michigan.

On top of all that, it was necessary that we redesign part of the chiller building itself. We had to believe that the balance of the poison flume, the tail under the neighbors’ detail shop, would continue to ooze northwest and pass under our then completed building. If it did, the odor would permeate our large underground room, frighten the RSA maintenance workers, and surely one of them would claim their health was damaged by the noxious stuff and file suit.

To compound the problem, we were advised by Haynes Kelley that Tetrachloroethylene fumes would dissolve bituminous base products. That meant the waterproofing membranes could be destroyed, as well as all the plastic pipe which was specified to carry rain and ground water around and under the structure.

To forestall such a catastrophe, we changed all the waterproofing on the chiller building to Bentonite, a clay base product, and switched all the plastic drainage pipe to fiberglass. We even installed an underslab vapor collection system to gather up all the toxic fumes and conduct them to the atmosphere. Another $50,000.

I am certain that we dug up only a small part of the evil flume, that the balance of the toxic bulb lies under the car wash property and beyond, and that it will continue to move northwest along with the waters of the sand strata. Perhaps eventually, it will be under the Tower itself, where we did not change the pipe or waterproofing, or install a vent system. Won’t that be exciting!

Not as exciting as it will be when the mess reaches the city water wells down by the river and the EPA turns downtown Montgomery into a Superfund Site.

-Charles Humphries (“Peril and Intrigue Within Architecture”)

This is one of many RSA Tower stories. The rest can be found here.