The Bulk Plant

Lynn Blackburn, our structural consultant on the project, is an awfully conservative engineer in his own right, but I probably pushed him even further in that direction when in one of our early planning conferences, he asked me how much sway we would allow the building to have. “What do you mean, sway?” I exclaimed more than asked. He replied, “Well, will you allow the top of the Tower to sway a foot back and forth in a high wind?” “How about no sway,” I retorted, a little horrified. We finally settled on four inches, but the temper was set–this would be a conservatively designed building.

Concrete columns in a mid-rise building like this one start out big and get progressively smaller on the upper floors. In Lynn’s design, the columns in the basement level were monsters–36 inches square–and were to be poured with 7,000 psi concrete. While 10,000 psi concrete is often produced in the big cities, a 7,000 pound mix would be almost double any concrete strength normally utilized in Montgomery.

Producing that high a grade in the local market caused us some concern. It’s not simply a matter of adding cement, which in large quantity can actually be detrimental. It involves special aggregate, absolute control of moisture and special cleaning and mixing equipment. We announced the criteria and demanded that all concrete mixing “bulk plants” be approved before bidding. Hodgson Concrete Company, a local firm, had the correct equipment but had hardly ever produced that strength. Sherman Concrete, a Birmingham company with a branch in Montgomery, often mixed 7,000 psi concrete in Birmingham, but its Montgomery branch had inadequate equipment. None of the five other local bulk plants had adequate facilities.

Sherman had the concrete supply contract on the RSA Union and could easily bring down a part of its Birmingham operation to meet the Tower specifications. But Sherman was performing so poorly on the Union project, already under construction, that the Union contractor fired them. As a result, just before the Tower was to bid, Sherman became disenchanted with its Montgomery operation and pulled its entire Montgomery branch. That left only Hodgson Concrete. Hodgson, at our insistence, produced a single batch of 7,000 psi concrete to prove they could do it, and the job was bid with Hodgson as the sole concrete supplier. Ron Blount, the RSA’s construction advisor, went through much gyration to insure that a fair price was offered, but that’s another story.

Bad Breaks

Thus it came to be that Hodgson Concrete of Montgomery supplied the concrete for the first of these enormous concrete columns poured on the Tower job. The column work started in July of 1993 and Hodgson quickly became careless and drifted back into the procedure it normally used to produce routine concrete.

On all large construction jobs, samples are taken from each concrete batch to assure that the concrete meets the specified strength. One sample is tested at the 7-day mark to give an early indication; and a second sample is tested at the end of 28 days, at which time the samples must have reached the specified strength. On the Tower project, the first 7-day breaks indicated we should expect strength problems, and HH&N’s project manager, Sonny Phipps, was so advised. Sonny indignantly replied there was no problem, and he continued to pour columns.

On all large construction jobs, samples are taken from each concrete batch to assure that the concrete meets the specified strength. One sample is tested at the 7-day mark to give an early indication; and a second sample is tested at the end of 28 days, at which time the samples must have reached the specified strength. On the Tower project, the first 7-day breaks indicated we should expect strength problems, and HH&N’s project manager, Sonny Phipps, was so advised. Sonny indignantly replied there was no problem, and he continued to pour columns.

The 28-day breaks bore out the prediction of low strength, but by 28 days Huber-Hunt had poured even more columns. Hodgson refused to admit there was anything wrong. Phipps insisted that the concrete would cure to strength at 54 days, and he begged that our official rejection of the columns be delayed until then. He kept on pouring columns. The 7- and 28-day breaks of the test cylinders continued to indicate unacceptable quality. The PH&J team began to get desperate. No way could we allow the bottom columns of our 24-story building to have deficient concrete.

Hodgson still refused to acknowledge a problem. Sonny Phipps refused to stop pouring. Hodgson claimed that HH&N’s job curing of the concrete was inadequate. When we pointed out that test cylinders did not reflect job curing, Bobby Hodgson claimed that our test lab was inexperienced and had miscalibrated equipment (we were using Jerry Gilbert’s CTE Lab, the best in Montgomery). Phipps insinuated the entire matter was PH&J’s fault because we had approved only one concrete supplier. He ignored the fact that there was only one to approve, and the fact that the magnitude of the problem was the direct result of his refusal to stop and correct the concrete mix when the first 7-day test break signaled a potential deficiency.

To counter these claims, we hired a second independent test lab, and then a third. One was Nelson Christian, the elder son of Hershel Christian who had plagued me in the Sixties. The Christian breaks verified those of Jerry Gilbert, and we gave Nelson the further duty of posting a technician at the Hodgson bulk plant to monitor its every move. We did not know it until later, but the Hodgson boys were making their own tests at the batch plant, and their breaks were as bad as ours.

Through all this, Huber-Hunt kept pouring columns with under-strength concrete, insisting that the concrete in the column forms was really not bad, that only the test cylinders were bad. Phipps implied that no test lab in Montgomery had the proper equipment to test 7,000 psi concrete. So we hired Ground Engineering and Testing Services of Birmingham. Same result.

Finally, we employed a test lab of national repute from Chicago called American Petrographic Services. This lab could dissect and analyze a concrete sample and tell you what was wrong with the mix process. That made six independent labs involved in this dreadful column episode. For the APS lab, the actual concrete columns were drilled to secure “core samples” and these were sent to Chicago. The American Petrographic tests of these drilled-out samples indicated that the columns were indeed deficient, and also suggested what Hodgson was doing wrong. With that information, Hodgson corrected its procedure and from then on, produced concrete of strength even greater than our specification required. Even so, the Hodgson brothers refused to admit that any of this was their fault.

Saw ‘Em Down

Our structural engineer reanalyzed the loading of many columns which tested borderline and allowed these to remain. However, HH&N still had to saw down some 31 three-foot diameter columns of high strength concrete. It was a time consuming operation which set the job schedule back almost two months. The operator of the diamond-studded rope saw used to take down these monsters was almost killed when the rope broke and its whiplash nearly cut him in two.

Our structural engineer reanalyzed the loading of many columns which tested borderline and allowed these to remain. However, HH&N still had to saw down some 31 three-foot diameter columns of high strength concrete. It was a time consuming operation which set the job schedule back almost two months. The operator of the diamond-studded rope saw used to take down these monsters was almost killed when the rope broke and its whiplash nearly cut him in two.

HH&N attempted to backcharge Hodgson Concrete for the fiasco and the two companies argued over the issue for over a year. In December of ‘94 Huber-Hunt employed Bradley, Arant, Rose and White, attorneys of Birmingham, to file suit against Hodgson in Federal Court. Hodgson employed Rushton, Stakely and Johnson of Montgomery to defend the action. Both parties attempted to draw PH&J into the fray on their side and to twist the facts accordingly. The entire PH&J staff felt that both of them had behaved reprehensibly.

I know not how the case was settled, but the affair did not bode well for our project. To forestall claims against the architect or owner (because we had prequalified Hodgson as sole supplier) the RSA agreed to waive two months of liquidated damages (at $12,000 per day). That was in addition to all the special lab costs, which the RSA paid, and all the extra engineering time which PH&J contributed.

The First Floor

When all 31 unacceptable concrete columns had been sawed down and repoured, forming of the pan-and-joist system for the first floor began. If you believe Sonny Phipps was humbled by the column episode, think again. The first floor plate size was 50,000 square feet, a huge area by any measure. PH&J suggested that the floor be poured in four separate operations, but the obstinate and omnipotent Phipps declared he would do it in two mammoth pours of 25,000 square feet each. It was a bad idea.

First and foremost, it was to be the first floor-plate pour that Phipps would manage on the Tower, meaning that he had zero experience with local facilities and labor necessary to such an operation. Second was the dire circumstance that virtually all the local cement finishers were already engaged on other jobs. Phipps went ahead with his pouring plan despite our warning, despite the shortage of finishers, and despite the inexperience of his crew of supervisors.

Unbeknownst to the PH&J field staff, Phipps made arrangements with Brice Construction Company, which was busily building the RSA Union six blocks up the street, to borrow their crew of cement finishers. Then, as fate would have it, Brice scheduled a floor pour for the same day that Phipps had chosen, and being the jackass he was, Phipps refused to change. Pompously he declared that he was establishing a one-week pour cycle, and that his pour day could not be changed because of some hick labor shortage.

This Terrible Void in the First Floor Structure Was Indicative of the Entire Unfortunate Pour – a Disaster Loomed.

On the appointed morning the concrete transit trucks began arriving and concrete began pumping out onto the first floor forms. Because there were hardly any finishers present, Sonny Phipps pressed all his carpenters into service, erroneously thinking that the Brice finishers would be only slightly late. As it turned out, they were very late, and the critical job of spreading and consolidating concrete over the vast floor area fell to the inexperienced carpenter crew. The concrete was not well vibrated into place, and it began to harden before it reached its final shape. It did not help that one of Phipp’s assistant superintendents had found a local girlfriend and, in the middle of the pour, had sneaked off for a “noonie”.

The pour was an unmitigated disaster. The indomitable Sonny Phipps had screwed up for the third time, and in each instance he had ignored well-considered advice from the architect. Sonny immediately blamed the whole problem on Hodgson, insisting that Hodgson had sent him bad concrete. We quickly pointed out that Hodgson had shipped the identical mix to the Union job that morning and that Brice Construction had no problem with it. Sonny stomped off in a huff.

When the forms were stripped away, huge voids, rock pockets and discontinures in the concrete were exposed to view. There was a real possibility that much of the newly poured floor structure would collapse if the shore supports were removed. While PH&J was gravely concerned, HH&N and Phipps wanted to consider it routine. It was not. As I told Project Manager Phipps, he could damn well tear it all down, or bring in the best experts money could buy in an attempt to salvage his catastrophe.

Huber, Hunt & Nichols called in national expert Kim Basham, who had a Ph.D. in Engineering and was head of CTC-Geotek of Denver. Basham retained Olson Engineering of Golden, Colorado, to take probes and make x-rays of the deficient areas. HH&N also hired Structural Services, Inc., floor construction consultants, of Dallas. When the reports were all in and repair methods described and approved, Structural Repair Services of Conley, Georgia, was brought in to make the actual repairs. Basham and his team then verified the results. Throughout this process, which took months, Huber-Hunt continually attempted to keep their special experts separated from PH&J’s field forces so they could filter the opinions. Over and over, I was forced to repeat, “We talk to them or it all comes down.”

PH&J hired Richard Muenow & Company of Charlotte, NC, to watch all of the contractor’s experts and judge their results. We had previously worked with Muenow when he made similar repairs on a job of ours in North Alabama. The Muenow team made almost 500 “Pulse Echo” tests of the repair work and finally in August of 1994 recommended acceptance of the effort.

There is no way to judge how much money was spent solving the concrete problems created by the bull-headed Sonny Phipps and his team. We continued to encounter one problem after another with concrete operations as the building rose, but nothing on the scale of the basement columns and the first floor joist and beam system. Each of these construction disasters was on the once-in-a-lifetime scale, and I had to encounter both on the biggest job I had ever attempted to administer.

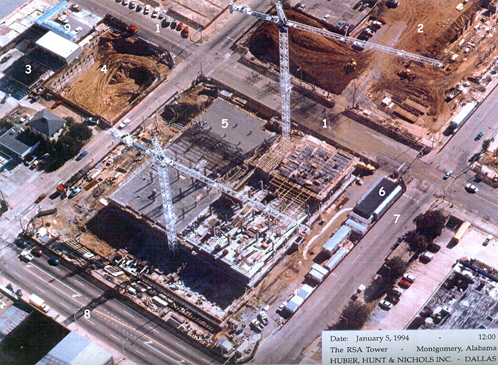

An aerial photo taken for the Huber-Hunt monthly report (the numbers were added). Mark 1 denotes Monroe Street. 2 is the site of the Waterfall Park. Mark 3 identifies the Madison Car Wash. Item 4 is the Tower Chiller Plant excavation. 5 is the SE corner of the Tower itself. Mark 6 is on the Contractor’s construction office. 7 is Lawrence Street, and 8 is Madison Avenue. 9 is the compound where the RSA & PH&J had their offices (the area later became the Pavilion Park).

Misaligned Stair Wells

As a matter of fact, Huber, Hunt & Nichols never found the mark for its concrete work, and concrete work constituted far and away the most significant block of work that it self-performed. For instance, their crew could never align the stairwell openings in one floor above another. As a result the stairway finish work on the Tower was an impossibility from the outset.

Nor could they even pour the floor slabs true to plane. Some floors are as much as two inches out of level. It was so bad that we sent civil engineer teams in to check the levelness, so everyone–us, the contractor and the owner–knew what was going on. HH&N just ordered the carpet sub to lay the carpet tile right over the defects. In some places the carpeted floors were so rough that one would literally stumble as he encountered humps in the concrete substrate.

On prior jobs, when such defects were discovered, the contractor was required to expend whatever effort was necessary to make connections. On the Tower we were told to ignore it. The PH&J field team struggled manfully to adjust to the new concept of management by Owner-Rep.

-Charles Humphries (“Peril and Intrigue Within Architecture”)

This is one of many RSA Tower stories. The rest can be found here.